Tel: +1 469 836 2108 | Email : drobnakbrass@gmail.com | Login

Harvey G. Phillips (1929-2010)

"Mr. Tuba"

Harvey Phillips on PBS, mid-1980s

1978 TubaChristmas Bloomington, Indiana

Video Tribute of Harvey Phillips

Celebration of Harvey Phillips

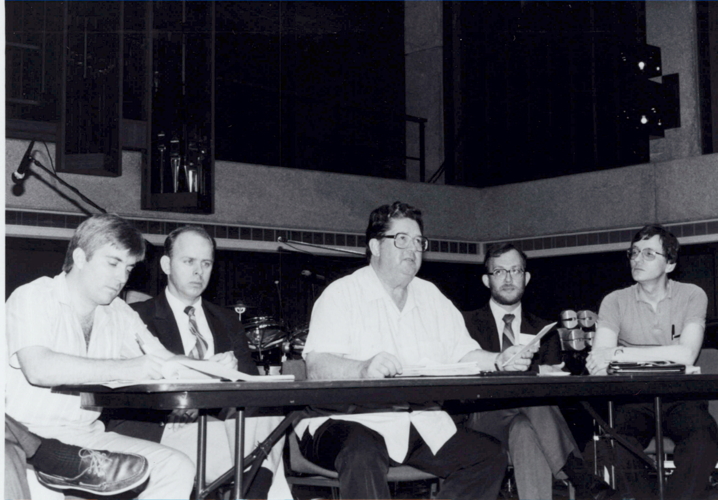

1986 ITEC Panel

Help support this website by buying me a cup of coffee!

Harvey G. Phillips (1929‐2010) was a world‐renowned tuba artist, teacher, progenitor, and consummate advocate of the tuba. For over twenty years (1950‐1971), Phillips was a freelance tuba artist in New York City (radio/television, commercial recordings on every major USA label). Other positions included Principal Tubist, Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus Band, Sauter‐Finegan Orchestra, New York City Ballet, New York City Opera, Band of America, Goldman Band, U.S. Army Field Band, Symphony of the Air, RCA Victor Orchestra, NBC Opera Orchestra, and Festival Casals Orchestra. He was a founding member (and tubist for 14 years) of The New York Brass Quintet (1953‐1967). Following his very successful performing career in New York City in 1971, Phillips succeeded the

great William J. Bell as tuba professor at Indiana University. In 1994 he retired with the title of Distinguished Professor of Music Emeritus. For ten years (1986‐96) Phillips served as Executive Editor of The Instrumentalist magazine.

Performances included two dozen Carnegie Hall (New York City) solo recitals, the first solo tuba recital at the Library of Congress, over two hundred clinic/recitals at colleges and universities throughout the world, with international tours of Japan, Australia, Scandinavia and Europe. He has been referred to by the press as "Paganini of the Tuba," “TubaMeister," "Iacocca of the Tuba," and "Mr. Tuba," a title conferred upon him by his teacher, the late William J. Bell.

Phillips was Co‐Founder/Past President– Tubists Universal Brotherhood Association (T.U.B.A.), Chairman/Host– First International Tuba‐Euphonium Symposium, Indiana University (1973), Chairman, First International Brass Symposium, Montreux, Switzerland (1974), Co‐Chairman/Host, Second International Brass Congress, Indiana University (1984).

Harvey was the founder and president of the Harvey Phillips Foundation, Inc., which administers OCTUBAFEST, TUBACHRISTMAS, TUBASANTAS, TUBACOMPANY, and TUBAJAZZ. In 1974, Phillips organized the first Merry TUBACHRISTMAS concert at Rockefeller Center (New York City) to honor his tuba teacher, the great William J. Bell. These concerts have become an annual tradition and are currently performed in over 250 cities in the United States and Canada.

Stating “no instrument can rise above its repertoire,” Phillips transformed the instrument’s repertoire by commissioning over 200 works for tuba. Commissions were procured from noted composers including Alec Wilder, Gunther Schuller, Vincent Persichetti, and David Baker.

Phillips’ musical artistry is documented in over 200 recordings, including five solo LPs on the Golden Crest label. He recorded work is represented in virtually every musical genre, including wind band, Dixieland, jazz, rock, chamber music, and orchestra.

The great bandmaster Merle Evans honored Phillips by selecting him as Principal Tuba of the Circus Hall of Fame Band. (Phillips played tuba under Evans in the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus Band).

Toward the end of his long and productive life, Mr. Phillips devoted a considerableamount of time and energy to writing his autobiography. Mr. Tuba was published (posthumously) by the Indiana University Press in 2012.

-Dr. Stephen Shoop (2016)

My special relationship with Harvey Phillips began in 1966 when I was in the US Army Band in Washington, D.C. I was studying for my Master’s degree at Catholic University and the man who taught tuba was a distinguished trumpeter but had no interest in teaching tuba and so I was pretty much left on my own. I needed direction. My band mate Dan Perantoni had been commuting to New York City and taking lessons from Harvey Phillips. He introduced me to him and I arranged for lessons in New York. He was well known for his many successes and “firsts” as a tuba player, particularly the New York Brass Quintet. I had also heard several recordings he had made as a soloist and with various commercial and classical groups and bands--mostly Golden Crest stuff.

Well, Harvey squeezed me into his busy schedule. At the time he was in the New York City Ballet Orchestra, the quintet, contracting orchestras and playing everywhere around New York, playing tons of studio calls. He was everybody’s 1st call. He had a deal with contractors that he could send a sub to rehearsals. If he couldn’t make the dress then the sub would do the concert. (Boy what a different world it is today—no one in LA could do that). He had a small rented studio way up the Carnegie Hall Tower that he shared (I believe with trombonist John Swallow). It had one music stand, two chairs and one bare light bulb. Most of my lessons were there although sometimes they were down in the bowels of the State Theater. At the time I was preparing my Master’s recital at Catholic University and Harvey helped me choose music. Much of it was stuff he commissioned and premiered so I got his special take on how to play the Hindemith, the Persichetti, the Effie Suite and Bach Contrapuntus IX and Bozza Sonatine for quintet. We also worked on the Vaughan Williams.

Harvey was the first real tuba playing teacher I ever had. In my undergraduate tuba lessons at IUP I studied with William Becker who was a trumpeter. He taught me well and was thorough with the basics but was not too familiar with the tuba literature—something he readily admitted. Harvey Phillips (in 1966) was the greatest tuba player in the world. I had recently gotten my 1st tuba—a Mirafone 186 CC. In the Army Band Bob Pallansch, Chester Schmitz and Dan Perantoni were my section mates. They all were great players and really inspired me. Chester particularly was the most amazing and talented tuba player I ever heard. He recently had won the Boston Symphony audition. They all got me fired up to get serious about the tuba and lessons with Harvey really put the polish on it. Bob Pallansch was very tight with Harvey too. They had been together in the US Army Field Band and he too recommend me to Harvey for lessons.

I commuted to NYC by train, bus or car for my lessons. One trip to the city for a lesson was very memorable. We had a tentative lesson scheduled for a Saturday. For many days I could not reach him by phone, so I took a chance and went to the city, got a room and finally reached him at 12:30 AM. He apologized that he didn’t have any time to teach me the next day but, if I had a black suit, I could sit in the pit of the State Theater with him for a performance of The Nutcracker. Well, not to be deterred, I bought the cheapest suit I could find (for $26) and sat next to him for the best lesson I could have ever had. Harvey played SOLID on that very good part. I was about 22 years old and Harvey was about 37. I thought he was an old man—what an interesting perspective young people have.

New York was a bright and happening place in the 1960s—the center of the music world. At one lesson I met Toby Hanks who had just been appointed to replace Harvey in the NY Brass Quintet. Harvey himself was getting ready to go to Boston where he became a Vice President of The New England School of Music under Gunther Schuller. It seemed a strange thing to me to think that anyone would leave all that playing in NYC but Harvey had a young family and wanted a different life for them. His organizing skills and business acumen were what was needed at NEC. I also met with Walter Sear at his shop in the NYC. He had hand copied the only tuba “excerpt” book that you could get in those days.

Earlier when I was studying with Harvey Phillips in New York I had some time to kill and went to a Friday matinee of the Sound of Music on Broadway. As I walked out onto Times Square (about 5 PM) I saw a string bass player (maybe from the show—who probably had a jingle date downtown) trying to get his bass into a cab. Broadway was 8 lanes all going south—the cab was in the middle lane. The poor bass player had his instrument over his head dodging cars that wouldn’t give him an inch. He finally made it. That helped me choose Los Angeles over New York. I also knew that wherever I went I would be poor for a while and would rather not freeze as well as starve.

My lessons with Harvey ended in the summer of 1967 but my relationship with him had just begun. He took me under his wing. I became part of his inner tuba circle and he included me in many of his projects down the line.

I wanted to be like him and do what he did—my life led me later to Los Angeles where (in many ways) I have had the opportunity to do much as he did in New York. Harvey was my ideal, not just as a tuba player, but also as a good citizen and as a man who lived his dreams. I wanted to please him with my life and career. NO ONE could ever achieve as much as he did but I sure wanted to try.

Anyone who knew Harvey got to share in that oversized personality and oversized appetite for living--and for food and drink. Many times he introduced me to restaurants and often with many friends and enormous amounts of food and drink. My attempts to keep up with him were always in vain. He loved to cook too. One summer I was hired as a guest clinician for the Summit Brass Workshop up in the Colorado Mountains. Harvey insisted that he take me and others for dinner at one of his favorite places. It was a steak house where you picked out your own steak and he picked the largest—a 20 ouncer. He cooked it on a grill, added a huge baked potato and salad and plenty of beer. I tried one too. After eating that enormous meal he promptly got up and chose another 20 ouncer and all the trimmings and easily ate it too. My attempts to keep up were trashed.

Harvey was a man of wisdom. He was very practical about things, very fair to everyone, had an engaging sense of humor and enjoyed some salty jokes. He made me feel comfortable. He never looked down or treated me in any way but as a colleague and adult. Many times he gave me great advice on my career moves and supported me in everything I did. That was really a shot in the arm!!

Everything he did was outsized.

One of the most important things Harvey did was the creation of the New York Brass Quintet (with trumpeter Robert Nagel). Not only was it the premier brass ensemble in the world it commissioned many many pieces—effectively starting the brass quintet explosion. Their efforts made it the standard chamber ensemble for brass players and put it on a par with string quartets and woodwind quintets. All of a sudden colleges wanted to add a tuba teacher to their faculties so they could have a resident brass quintet. Well I was the recipient of one of those earlier college jobs. In 1969 the University of Tennessee hired me to teach tuba and play in the faculty brass quintet. Within three years I had a full load of tuba and euphonium majors—effectively creating a long-term position for myself--and others who followed. So thanks go to him (in a big way) for creating the brass quintet.

During my years at Tennessee I stayed in pretty good touch with Harvey, we had him and the NYBQ in one year for a concert and clinic. I remember him saying that the only time the guys in the quintet had time to rehearse was 2 in the morning the night before. That night they did Bach’s Contapunctus IX, the Bozza, the Malcolm Arnold, the Etler and the Gunther Schuller—all in one concert— absolutely amazing!

His clinics were amazing for their facts about everything tuba and he always played lots of fun stuff like Carnival of Venice on a sousaphone—or simple jazz ballads or Air and Bouree. He was never a snob and loved all kinds of music.

Many times during these years I got great advice about things. When Harvey moved to Bloomington in 1971 I was in the middle of my years at UT. He right away started planning things for the 1st International Tuba/Euphonium Symposium Workshop—which took place in 1973. Harvey asked me to be on the planning committee with Perantoni, Winston Morris, Les Varner, Ron Bishop, and several others. I felt always that I had the least to offer but we had some fun meetings at the Tuba Ranch with lots of food and cheer. At the conference unfortunately Harvey got sick and sent me as a sub for the premier of the Gunther Schuller Tuba Quartet—a huge shot and challenge for me. We all know the tremendous event the 1973 conference became—in my opinion the single most important thing that ever happened for the tuba/euphonium community—a spectacular event and the beginning of a real organized future for our instruments.

Harvey had a really good outlook on life. Always positive. Always forward thinking. Always looking at the big picture and always thinking about others. He always had a slogan. Good citizenship was important to him and doing for others. He was always insistent that students had to make their own way in life—to create work and be entrepreneurs. These things have always been a part of my life, how I try to live, how I teach and the values I respect.

In 1974, one year after the first International Symposium, I hosted the first Regional Tuba/Euphonium conference in the country—the Mid- South Workshop at the University of Tennessee. The organizational things I learned from Harvey helped make that a big success—and ITEA has continued those all over the country ever since. In 1978 I hosted the 3rd ITEC at USC in L.A. and Harvey of course was a star attraction and a constant help in organizing the event. Over the years I would see Harvey at many of the ITECs. A couple of times I subbed for him for rehearsals on the TubaJazz Concert. That 1st tuba part was so high and demanding. Another time I played bass on a rehearsal—lots of fun.

Later, after moving to Los Angeles in 1974, I remained in touch with Harvey by phone and letter. That year he began TubaChristmas in New York City. Two years later I organized the Los Angeles TubaChristmas and it has been going for over 35 years. Several years Harvey came out and guest conducted. But the long trip, cost and his grueling schedule of TC concerts made LA difficult to do for him.

ITEA (formerly TUBA) would not have happened without his leadership. He really liked the rather corny Tubist’s Universal Brotherhood Association (that he coined) and was not happy with the more politically correct ITEA but went along with it.

In 1984, after I had some years as a studio musician Harvey invited me to be an artist and clinician at 1st International Brass Conference at IU. That was another huge event—this time for all brass players. I remember playing my EVI and having John Fletcher in the audience. I also got to play with Doc Severinson, sub on bass with the TubaJazz Consort and have a brief jazz set of my own. (one of my early, limited forays into jazz).

Harvey, Carole and Thomas visited my home several times. I always enjoyed talking to Harvey. He was a kind of guru—full of advice, not only about music and tuba playing, but about life and how to live it. His compass was always focused on the future and what he could do (or could encourage others to do) to make things better for our instrument.

I dedicated my second classical CD, “The Big Stretch” to Harvey. The album featured several of my new compositions with tuba. He wrote a short blurb for the CD booklet about my composing. It was very flattering. Harvey many times wrote or said compliments for me. They helped me at many stages in my career. I really appreciate those boosts.

One of the things Harvey had was a great gift of English. He wrote and spoke with eloquence and added class to the tuba world. He was always a great spokesman for the tuba and he did it with grace and intelligence. One of his goals was to raise the image of the tuba and he had the social gifts to do it. He seemed to know everyone in the musical world and was able to commission hundreds of new works.

Twice I flew my plane into Bloomington and stayed at the Tuba Ranch. Once (in 2001) Harvey donned his chef’s hat and prepared lobster and pasta.

In the summer of 2009 I went back for a little reunion at Dan Perantoni’s home with Winston Morris and Bob Tucci. We had a wonderful time with our “mentor”.

He was sharp as a tack. While he had difficult health problems in his last years he spent every day writing and “getting stuff done”—what a good way to live.

He was determined to leave the world a better place, to have a positive impact and make his life meaningful to others. No one has done that better than Harvey Phillips. His legacy will live on forever.

-Jim Self (A Personal Memoir of Harvey Phillips, 2011)

Harvey performs Carioca with the Gulf Coast Concert Band (1993)

Harvey performs Lazy River with The United States Coast Guard Band

Harvey Phillips, a Titan of the Tuba, Dies at 80

By DANIEL J. WAKIN

Published: October 24, 2010

The New York Times

The tuba players mass by the hundreds every year on the Rockefeller Center ice-skating rink to play carols and other festive fare, a holiday ritual now ingrained in the consciousness of New York.

Mr. Phillips conceived the “Tuba Christmas” concerts at the Rockefeller Center skating rink. The tradition began in 1974, the brainchild of Harvey Phillips, a musician called the Heifetz of the tuba. In his time he was the instrument’s chief evangelist, the inspirer of a vast solo repertory, a mentor to generations of players and, more simply, Mr. Tuba.

Most tuba players agree that if their unwieldy instrument has shed any of the bad associations that have clung to it — orchestral clown, herald of grim news, poorly respected back-bencher best when not noticed, good for little more than the “oom” in the oom-pah-pah — it is largely thanks to Mr. Phillips’s efforts. He waged a lifelong campaign to improve the tuba’s image.

Mr. Phillips died on Wednesday at his home, Tubaranch, in Bloomington, Ind., his wife, Carol, said. He was 80 and had Parkinson’s disease.

Like many towering exponents of a musical instrument, Mr. Phillips left a legacy of new works, students and students of students. But even more, he bequeathed an entire culture of tuba-ism: an industry of TubaChristmases (252 cities last year) and tuba minifestivals, mainly at universities, called Octubafests.

“The man was huge in putting the instrument on the map as a solo instrument,” said Alan Baer, the New York Philharmonic’s tuba player, two of whose teachers were Phillips students. “Our repertory is so limited, and it would be horrible if he had not done the amount of work that he did.”

Mrs. Phillips said her husband had either commissioned or inspired more than 200 solo and chamber music pieces, many wheedled out of composers by persistence or other methods. “I remember Persichetti was a case of Beefeater gin,” she said of the composer Vincent Persichetti.

Mr. Phillips once said, “I’m determined that no great composer is ever again going to live out his life without composing a major work for tuba.”

Harvey Phillips was born on Dec. 2, 1929, the last of 10 children, in an Aurora, Mo., farming family. The family moved often, and he attended high school in Marionville, Mo.

After graduating, Mr. Phillips took a summer job playing tuba with the King Bros. Circus. He left to attend the University of Missouri but was quickly lured away by another circus offer: playing tuba with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. It was the pinnacle of circus bands.

One of the band’s duties was to give “alarms”: play pieces to alert circus staff in the case of, say, a high-wire accident. “Twelfth Street Rag” was the alarm for that, a signal to send in the clowns to distract the audience, Mr. Phillips said in a New Yorker profile in 1976. He spent three years with the Ringling band.

On a circus trip to New York, where he played duets with the clanging pipes in his hotel room, Mr. Phillips met William Bell, the tuba player of the New York Philharmonic. Mr. Bell soon arranged for him to study at the Juilliard School and become his pupil.

Mr. Phillips spent two years in the United States Army Field Band in Washington but returned to New York, drawn by the many opportunities. He became a successful freelancer, playing regularly with the New York City Opera and New York City Ballet orchestras, recording and making broadcasts.

In 1954 he helped found the New York Brass Quintet. The combination (two trumpets, French horn, trombone and tuba) was less common at the time than it later became. Brass quintets proliferated, a boon for tuba players, because brass players on university faculties needed a tubist colleague to form a group. More tuba professors meant more tuba students.

Mr. Phillips also played jazz, performing in clubs and recital halls. As his reputation grew, composers began writing for him, and Mr. Phillips introduced another rarity, the tuba recital. In 1975 he played five recitals at Carnegie Recital Hall in nine days.

Writing in The New York Times in 1980, the music critic Peter G. Davis said first-time listeners to Mr. Phillips “could scarcely fail to be impressed, and probably not a little astonished, by the instrument’s versatility and tonal variety, its ability to spin a soft and sweetly lyrical melodic line, to dance lightly and agilely over its entire bass range, and to bellow forth with dramatic power when the occasion demands.”

Mr. Phillips’s entrepreneurial abilities emerged in his New York years, too. He served as the orchestra contractor for Leopold Stokowski, Igor Stravinsky and Gunther Schuller, among others. When Mr. Schuller took charge of the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, he recruited Mr. Phillips as vice president for financial affairs. Mr. Phillips held the position from 1967 to 1971, commuting to New York for evening performances.

The punishing routine took away from practice and family time. Coming home late one night and missing his family, he took out his tuba while his wife and two of his children slept in the bed nearby and practiced until dawn, playing so softly that they did not wake up, according to the New Yorker profile.

He often practiced in the backseat of his car while his wife drove and their children kept eyes on the road to warn of approaching potholes. “They would yell, ‘Daddy, bump!’ ” Ms. Phillips said.

In addition to Ms. Phillips, Mr. Phillips is survived by their sons, Jesse, Harvey Jr. and Thomas.

In 1971 Mr. Phillips joined the faculty of Indiana University. He retired in 1994.

In his tireless efforts to raise the tuba’s profile as well as to honor Mr. Bell, his teacher, Mr. Phillips — perhaps touched by the showmanship of his circus past — decided to gather tuba players for a special holiday concert in Rockefeller Center. (Mr. Bell was born on Christmas Day, 1902.)

He called an official there with the suggestion. “The phone went silent,” he later recounted. “So I gave the man some unlisted telephone numbers of friends of mine.” They included Stokowski, Leonard Bernstein, André Kostelanetz and Morton Gould. “He called me back in about an hour and said, ‘I’ve spoken with your friends, and you can have anything you want.’ ”

The Tuba Christmas extravaganzas took off. Volunteers hold them around the country under the auspices of the Harvey Phillips Foundation. Sousaphones and euphoniums are also welcome.

At the tubafests, the musicians play “Silent Night” in honor of their fellows who have died, Mrs. Phillips said. On Dec. 12 when tuba players gather again at the skating rink, the carol will be played in Mr. Phillips’s memory.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: October 31, 2010

An obituary last Sunday about Harvey Phillips, the founder of an annual gathering of tuba players known as TubaChristmas, misstated the date for the event this year at Rockefeller Center. It is scheduled for Dec. 12, not Dec. 8.

-The New York Times