Tel: +1 469 836 2108 | Email : drobnakbrass@gmail.com | Login

Constance "Connie" Weldon (1932-2020)

First female tuba player to perform with a major orchestra

Sam Pilafian on Connie Weldon

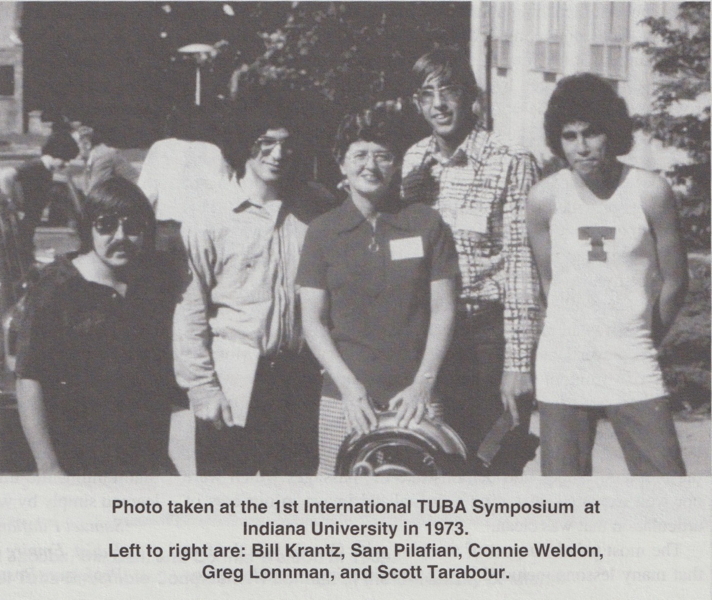

I would like to share a look at Constance Weldon the teacher. I studied with Connie from the age of 13 until I was 21. Her wonderful teaching approach came from a blend of virtuoso playing, fine conducting skills and her vocal ability. There was much singing at her lessons. I remember as a young player being pulled through pieces by her strong singing voice. This vocal role model inspired lyrical approach to tuba playing. There was much music theory using the tuba without printed music. Many scales, arpeggios and patterns started each lesson (with extended ranges to complete sequences). That and much memorizing of selections provided strong ear training using the instrument. This was tested regularly with a sight reading “pop quiz” which we were expected to execute with mental ferocity. Mistakes such as misread rhythms or improper reading of the “road map” were reviewed carefully so they would not be repeated.

Connie was an articulation fanatic. She was the cleanest Bb-flat tuba player I have ever heard. Her teacher, Bower Murphy, was a fine trumpet player and composer who spent time each week writing etudes for her to inspire a clean articulation. Connie used these etudes as well as Arban and Kopprasch to teach clear contrabass tuba playing. She would carefully critique the prepared etudes and demonstrate the passages which were not well executed, installing a crystalized image in our ears of articulation that was clean.

The most painful aspect of studying with Connie was the fact that many lessons included taping and listening to etudes, solos or excerpts on her “Hi-Fi” with an old Wollen-Sack reel-to-reel recorder… the Grim Reaper! This introduced harsh reality to our lessons by forcing us to listen to what was coming out of the bell. There simply was no deluding yourself at a Connie lesson. Yet so much positiveness came from her while listening back that we came to enjoy the process of improving even in the smallest increments.

Tuba ensemble was the foundation of Connie’s teaching studio. The refining of such musical elements as rhythm, pitch, tone and phrasing in a group setting created a spirit of cooperation and teamwork. Working hard together and having fun became synonymous. Here Connie taught invaluable lessons on being a good colleague.

I was fortunate to spend many hours playing duets with Connie and performing next to her two nights per week in Lamonaca’s Concert Band. The sound pictures she created when playing are still my role model.

The most important lessons from Connie were so universal that many of her students applied them and became successful in the sciences, business and the law as well as music. She inspired us all to do our best work with a high level of intensity while maintaining the utmost respect for those around us. This we learned simply by watching her.

-Samuel Pilafian, Tubist - Empire Brass, Professor, Boston University (1991)

Born and raised in Winter Haven, Florida, Constance Weldon started playing drums in the fourth grade. She then picked up the trumpet, later playing horn, valve trombone, baritone horn…all on the way to her final destination, the tuba! From that day on, Connie's life was never the same as it constantly revolved around playing the tuba. As valedictorian of Miami Jackson High School, she was offered scholarships to all of Florida's universities. She decided to accept an academic scholarship to the University of Miami.

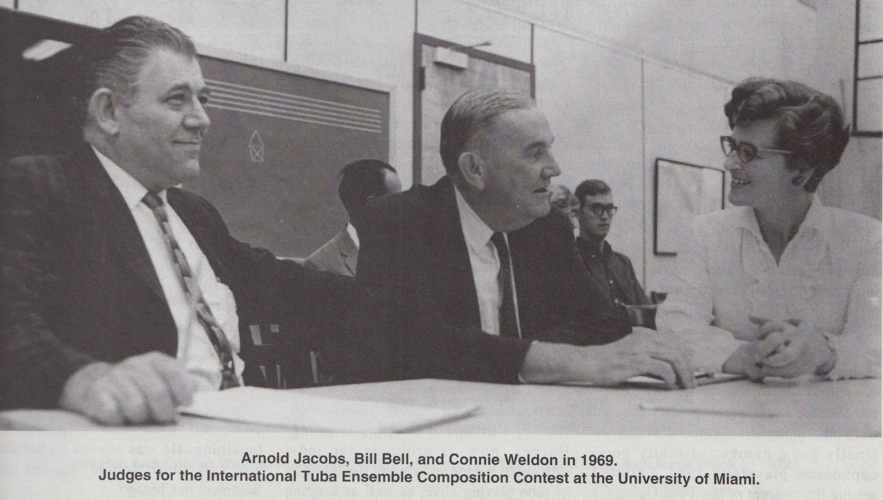

While studying with Bower Murphy, the trumpet playing teacher of all brass at the University of Miami, Connie auditioned for and was accepted to the Tanglewood Music Festival in the summer of 1951. There she played under the baton of a young Leonard Bernstein as well as other promising and established professional conductors. At summer's end, she turned down a position in the Rio de Janeiro Symphony to finish her education.

Connie completed a Bachelor of Music degree in 1952 and a Master of Education in 1953 from the University of Miami. Returning to Tanglewood in 1954, she auditioned for Arthur Fiedler and joined the Boston Pops Touring Orchestra. Connie next joined the North Carolina Symphony. In 1957 she was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship Award to study in Amsterdam with the Concertgebouw tubist, Adrian Boorsma. During that time she joined the Netherlands Ballet Orkest and was acting principal tuba of the great Concertgebouw Orchestra.

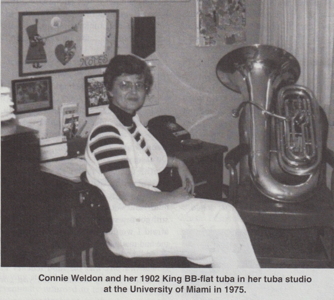

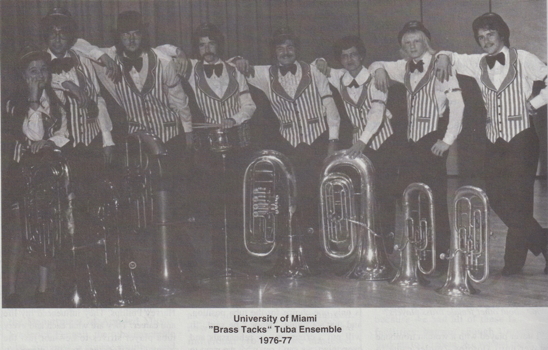

Upon returning to the U.S., Connie joined the Kansas City Philharmonic for two seasons, after which she returned to Florida to join the Miami Philharmonic and teach at the University of Miami. Connie quickly established a reputation as an expert teacher, known for her prescriptive and thorough approach. In Connie's studio, musicianship and technical teaching received equal time. As a result of her successful studio building, Connie formed the University of Miami Tuba Ensemble in 1960, the first credited group of its type at any university. In this ensemble, Connie taught a higher awareness of intonation, balance, rhythm, accompaniment skills, and solo playing with musical

opinion. Her success with the University of Miami Tuba Ensemble led to interest from other universities and a proliferation of this type of ensemble throughout the tuba world. Connie's success as a teacher also led to her becoming the conductor of the University of Miami Brass Choir, one of that school's flagship ensembles.

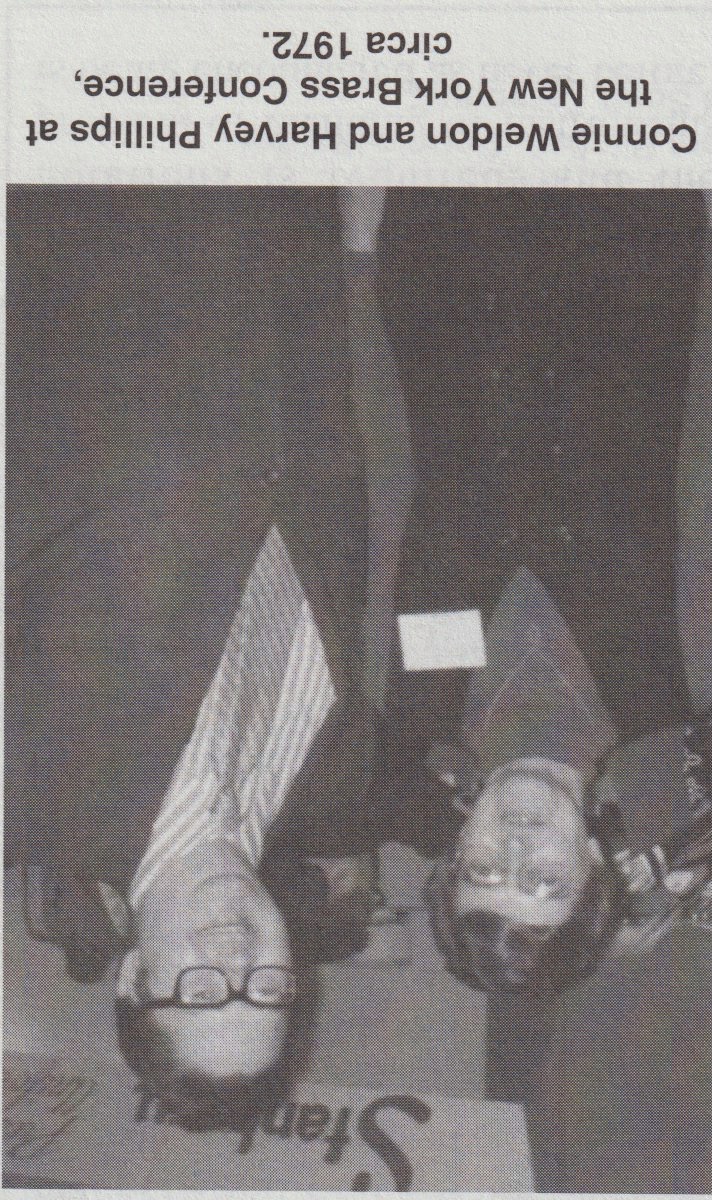

From 1972 until her retirement in 1991, Connie was the Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies at the University of Miami. In this position she provided guidance to thousands of future musicians and teachers. Since then, she has been honored with the University of Miami Distinguished Alumna Award, the University of Miami Distinguished Woman of the Year, the World Who's Who of Women in Education, and the Pioneer Award of the International Women's Brass Conference.

-ITEA Honorary Life Members

Weldon’s Words of Wisdom

1) Hone your skills until your reputation for competence is bullet-proof. Don’t continue past your prime. When it’s time to move on, let people remember you at your best.

2) Any goal worth achieving takes time. There are no shortcuts. Stay committed to your reams and objectives for the long term.

3) Be your own worst critic and your own best admirer. Be confident in your own feedback, because it is the only feedback in life that you can really count on.

4) Have the compassion to help others. Help those who helped you. If you can’t help those who helped you then pass your kindness and knowledge on to the next generation.

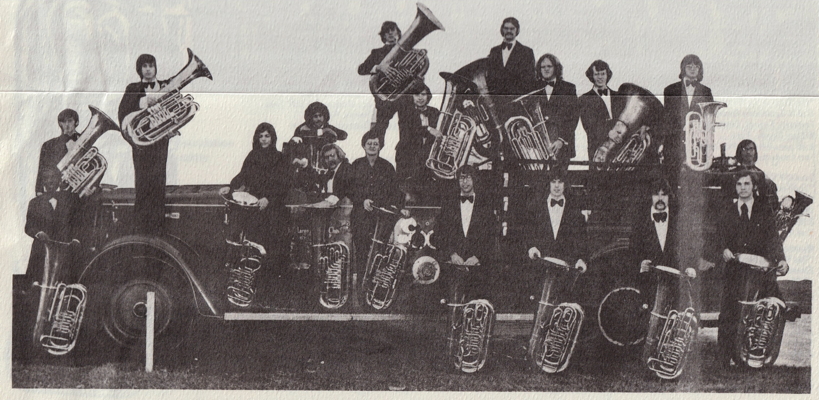

Circa 1974 University of Miami Tuba-Euphonium Ensemble

From Tuba Awareness Week Brochure

Constance Weldon 1991 TUBA Journal Cover Photo

Weldon on playing for Arthur Fiedler on tour with Boston Pops:

On the Boston Pops tour, we usually played in gymnasiums, because we were sold out everywhere – never an empty seat! Usually, Fiedler would come in the traditional way, which is in front of the violins. For some reason, on this occasion there were two sets of risers in the back, and we were up high, almost half a story. Mr. Fiedler wore taps and all of a sudden I hear this tap, tap, tap, behind me. I thought to myself that he was coming up behind me, and that my music stand was in his path. Quickly I moved to pull my music stand out of his way. Just as I pulled the top of the stand over, the bottom part stuck out and tripped him. There he went tripping down all of those risers and yet he kept his balance; I don’t know how. All the way down he was glaring back at me. When I tried to move my stand once Knew that he had tripped, m stand hit the next one, and the next one, etc. – the domino effect. All of the music went way down behind the risers. As a result, the whole audience had to wait until they picked up and sorted though the music and put it back. All along, here is this bright red tuba player’s face.

Weldon on the challenges to being a female musician playing a brass instrument

It never was a great problem, and it always seemed to resolve itself. In fact, sometimes it was kind of funny how it resolved itself. With Fiedler, back in 1954, it never seemed to enter his mind that I was a woman. At least, he never gave that impression. He was very supportive all of the way. On one occasion, when I auditioned for the Kansas City Philharmonic, I was told right up front, before I played, that, “We’ve got a lot of men auditioning for this You can’t just be better, you’re going to have to be much better.”

“Fine with me,” I said, “unless I am, I don’t want the job!” I got the job.

There was never any doubt in the orchestra about the acceptance I had. I always felt comfortable whenever I played. They didn’t make over me especially, nor did they put me down especially. I was just treated like the tuba player. In Europe, I recall one humorous situation after I had first arrived to play with the ballet orchestra The first time I played in the pit I was warming up and somebody came and leaned over, looking at me in disbelief. All of a sudden, they were motioning to the audience (this is before the performance had begun), and everybody was leaning over and pointing at me. I felt like I was a monkey in a zoo. Of course, the sight of a female tuba player in Europe at that time in the fifties was unusual. There was a female trumpet soloist who went around, but tuba? They never suspected that any woman would ever play that!

I never played with a woman trombone player until Dorothy Zeigler came to Miami to teach. There were women horn players who didn’t seem to have any problems, and there were a couple of women trumpet players who seemed to have a little more trouble with their peers in their section than did the women horn players.