Tel: +1 469 836 2108 | Email : drobnakbrass@gmail.com | Login

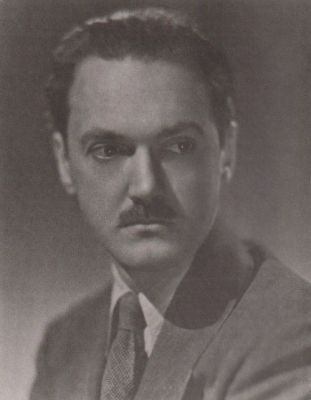

Alec Wilder (1907-1980)

American Composer

Alec Wilder

Roger Bobo performs Wilder's Effie Suite

Kent Eshelman performs Songs of Alec Wilder at the 2016 ITEC

The Octets (Music for Lost Souls and Wounded Birds)

Alec Wilder (New York Public Library)

37th Annual Alec Wilder Concert 2022

Alec Wilder Music and Life

Alec Wilder Works for Tuba and Euphonium

Sonata for Euphonium and Piano (c. 1968) for John Swallow.

Convalescence Suite (1971-1975) for Harvey Phillips. Three Suites of 6 Movements each

Elegy For The Whale (1975) Tuba and Orchestra. Also available Tuba and Piano

Encore Piece For Tuba and Piano (1960) for Roger Bobo. Also known as “A Tubist’s Showpiece”

For Jesse Alone. Unpublished

Small Suite for Tuba and Piano (1968)

Sonata No. 1 for Tuba and Piano (1959) for Harvey Phillips

Suite No. 1 for Tuba and piano (1960) for Harvey Phillips. “Effie Suite” (1966) Tuba and Orchestra

Suite No. 2 for Tuba and Piano (1964) for Jesse Emmett Phillips

Suite No. 3 for Tuba and Piano (1966) Written for Harvey Gene Phillips, Jr. “Suite for Little Harvey”

Suite No. 4 for Tuba and Piano (1968) Written for Thomas Alexander Phillips “Thomas Suite”

Suite No. 5 for Tuba and Piano (1963) for Ethan Ayer

Concerto for Euphonium and Wind Orchestra (1971) for Barry Kilpatrick

Concerto for Tuba and Wind Ensemble (1968) for Harvey Phillips. Piano reduction by Robert George Waddell.

Ballad for Whitney B. (1979) for the Phillips-Matteson Tuba Jazz Consort

Effie Joins A Carnival (1960) arr. for tuba and brass quintet by Ronald Bishop

Elegy (1971) tribute and in memory of William Bell. Tuba and 9 Horns

Suite for Horn and Tuba (1978) for Martin Haddeman and Gary Maske

Suite (10 Duets) for Tubas (1970)

Suite No. 1 for Horn, Tuba and Piano (1963) for John Barrows and Harvey Phillips

Suite No. 2 for Horn, Tuba and Piano (1971) for John Barrows and Harvey Phillips

Ten Trios for Tubas (1971)

Tuba Trio No. 1 (1971)

Effie Suite (1959) for tuba, vibraphone, piano and drums. In 6 movements. For Harvey Phillips

Suite for Tuba, Bass and Piano (1962)

Help support this website by buying me a coffee!

Alec Wilder's music is a unique blend of American musical traditions — among them jazz and the American popular song — and basic "classical" European forms and techniques. As such it fiercely resists all labeling. Although it often pained Alec that his music was not more widely accepted by either jazz or classical performers, undeterred he wrote a great deal of music of remarkable originality in many forms: sonatas, suites, concertos, operas, ballets, art songs, woodwind quintets, brass quintets, jazz suites — and hundreds of popular songs.

Many times his music wasn't jazz enough for the "jazzers," or "highbrow," "classical" or "avant-garde" enough for the classical establishment. In essence, Wilder's music was so original that it didn't fit in any of the preordained musical slots and stylistic pigeonholes. His music was never out of vogue because, in effect, it was never in vogue, its non-stereotypical character virtually precluding any widespread acceptance.

Alec Wilder was born Alexander Lafayette Chew Wilder, in Rochester, New York on February 16, 1907. He studied briefly at the Eastman School of Music, but as a composer was largely self-taught. As a young man he moved to New York City and made the Algonquin Hotel — that remarkable enclave of American literati and artistic intelligentsia — his permanent home, although he traveled widely and often.

Mitch Miller and Frank Sinatra were initially responsible for getting Wilder's music to the public. It was Miller who organized the historic recordings of Wilder's octets beginning in 1939. Combining elements of classical chamber music, popular melodies and a jazz rhythm section, the octets became popular — and eventually legendary — through these recordings. Wilder wrote over twenty octets, giving them whimsical titles such as Neurotic Goldfish, The Amorous Poltergeist and Sea Fugue, Mama.

Frank Sinatra, an early fan of Wilder's music and an avid supporter, persuaded Columbia Records to record some of Wilder's solo wind works with string orchestra for an album in 1945, Sinatra conducting. The two men became life-long friends and Sinatra recorded many of Wilder's popular songs. His last song, A Long Night, was written in response to a 1980 request from Sinatra for a "saloon" song.

It is a relative rarity for a composer to enjoy a close musical kinship with classical musicians, jazz musicians and popular singers. Wilder was such a composer, endearing himself to a relatively small but very loyal coterie of performers, and successfully appealing to their diverse styles and conceptions. He wrote art songs for distinguished sopranos Jan DeGaetani and Eileen Farrell, chamber music for the New York Woodwind and New York Brass Quintets, larger instrumental works for conductors Erich Leinsdorf, Frederick Fennell, Gunther Schuller, Sarah Caldwell, David Zinman, Donald Hunsberger and Frank Battisti, many of them premiering his works for orchestra or wind ensemble.

Jazz musicians fascinated Wilder with their gift for creating extemporaneous compositions. Among those for whom he composed major works were Marian McPartland, piano; Stan Getz, Zoot Sims and Gerry Mulligan, saxophone; Doc Severinsen and Clark Terry, trumpet. Entire albums of his songs and shorter pieces were recorded by Bob Brookmeyer, Roland Hanna and Marian McPartland. Individual Wilder songs have been recorded notably by Cab Calloway, Red Norvo, Keith Jarrett, Don Menza, Jimmy Rowles and Kenny Burrell.

Wilder's relationship with popular and jazz singers was especially close. Despite his songs' sinuous angular melodies and unorthodox forms, he was admired and respected not only by Frank Sinatra and Cab Calloway, but by Mabel Mercer, Jackie and Roy Kral, Mildred Bailey, Peggy Lee, Tony Bennett, and, more recently, Marlene VerPlanck and Barbara Lea. For Mabel Mercer (whom Wilder called the "Guardian of Songs") he wrote many of his finest popular as well as art songs. She responded by making definitive recordings of a number of them. Among his best known songs are It's So Peaceful in the Country (written for Mildred Bailey), I'll Be Around, While We're Young and Blackberry Winter. Sometimes Wilder wrote lyrics for his songs, but more often he collaborated with outstanding lyricists such as William Engvick, Johnny Mercer, Arnold Sundgaard and Loonis McGlohon.

Wilder's interest in children brought about hundreds of piano pieces, easy study pieces for many different instruments, the well-known A Child's Introduction to the Orchestra and the song book Lullabies and Night Songs, illustrated by Maurice Sendak. His cantata Children's Pleas for Peace is a testament to his hopes for a better world for young people. He also wrote many children's songs for television productions and records, such as The Churkendoose performed by Ray Bolger and a version of Pinocchio starring Mickey Rooney. Additionally, the children of many musician friends were remembered with numerous solo chamber works.

In the early 1950's, Wilder became increasingly drawn to writing concert music for soloists, chamber ensembles and orchestras. Up to the end of his life, he produced dozens of compositions for the concert hall, writing in his typically melodious and ingratiating style. His works are fresh, strong and lyrical.

Wilder shunned publicity and was uncomfortable with celebrity. Nonetheless, his awards eventually included an honorary doctorate from the Eastman School of Music, the Peabody Award, an unused Guggenheim fellowship just before his death, an Avon Foundation grant, the Deems Taylor ASCAP Award and a National Book Award nomination — all having to do with American Popular Song — (The Great Innovators 1900-1950) (co-written with James T. Maher), undoubtedly the definitive work on the subject. He included almost everyone who had written a song of quality, but not one word about himself or any of the hundreds — maybe thousands — of pieces he wrote.

No one will ever be sure just how much music Wilder wrote. Sketches of music — sometimes entire pieces — were often written on small scraps of manuscript while he rode a train, sat on a park bench or waited in an airport terminal. Scattered about in private collections of Wilder's friends were dozens of compositions which never reached performance or publication. Some may still lie in piano benches and desk drawers wherever Wilder visited, for he wrote almost entirely for friends, and most of his pieces were gifts to them or their children.

Although he protested the label (perhaps sometimes too vigorously), Alec Wilder was a bona fide eccentric. If some of his music sometimes has a lopsided, irregular shape, it is because he intended to throw us off guard in making a musical or emotional point. In his popular songs he often created seven-and-nine-bar phrases which, nonetheless, always feel as natural as the more orthodox eight-bar structures of Tin Pan Alley. That he could also work well within these more traditional forms is borne out by hundreds of songs and instrumental pieces. Alongside his more complex sinuously winding melodies, Wilder could also create tunes of haunting simplicity. I'll Be Around is surely an extraordinary example of the latter, while the ravishing theme of Alec's Serenade (from the Jazz Suite for Four Horns) is a superior representative of the former, a melody worthy of an Ellington or a Gershwin, or a Schubert, and arguably one of the most beautiful melodies ever composed in our century.

Wilder died of lung cancer on Christmas Eve in 1980 in Gainesville, Florida. In 1983, he was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters' Hall of Fame and in 1991 the Sibley Music Library at the Eastman School of Music dedicated the Alec Wilder Reading Room.

— Biography written by Gunther Schuller, Loonis McGlohon & Robert Levy